We all know some vague, detail-less version of this story:

Somewhere, a loving parent takes a picture of their child with a smartphone and posts the picture online. Some nefarious individual gets a hold of the picture and hacks into it to figure out exactly where the picture was taken. The region finds itself in the grips of an Amber Alert.

Somewhere, a loving parent takes a picture of their child with a smartphone and posts the picture online. Some nefarious individual gets a hold of the picture and hacks into it to figure out exactly where the picture was taken. The region finds itself in the grips of an Amber Alert.

Technology is supposed to help us? Can this really happen? And how can I share photos of my kids (they’re so cute after all) and fell safe doing it?

Understanding Digital Photos

If you’re old enough to remember film, you know that a film picture doesn’t carry a whole lot of data with it. It’s basically just a picture. On the back (depending on where you got it developed) may be a printed date, but that was the developing date not the date the photo was taken. The obsessive-compulsive among us found ways to keep track of dates and locations, but that information was not inherently a part of the picture.

Enter digital photographs. A digital photo file is much more than a physical photograph, so much more. Each file contains a picture, but it also contains something called “metadata,” or data about data. If I dust of my old digital Canon Rebel XSi and take a picture, this is the metadata it records (in addition to the picture itself):

- Date/time the photo was taken

- Photo dimensions

- Color mode

- Focal length

- Which lens was on the camera

- Whether the flash fired

- Metering mode

- White balance

- Aperture and shutter speed

- Film speed (ISO)

- My camera’s serial number

And you thought it was just a mere picture. Also, there’s space in the metadata for me to add things like:

- My name/address/website

- Copyright information

- Description

- Keywords for searching

- and lots more…

Now there are lots of reasons why this is great data to have access to. As the owner of the photo I have lots of very useful information about each photo (such as all the camera settings). As an end user I can easily find the owner and copyright information of each digital photograph (if that information is filled in). Having all this information on a film-based picture would be highly impracticable, if not impossible.

What About Smartphones

Smartphones have one key feature that my Canon digital camera doesn’t have: access to GPS. There’s a space in the metadata for that information too (even the direction you’re facing too). And your GPS is pretty reliable – it can probably tell you what room of your house you are in. Try it now: open the maps app on your phone, switch to satellite view, and zoom in as far as you can. Your phone has a pretty good sense of where on the planet it is (which is pretty amazing if you think about it).

Smartphones have one key feature that my Canon digital camera doesn’t have: access to GPS. There’s a space in the metadata for that information too (even the direction you’re facing too). And your GPS is pretty reliable – it can probably tell you what room of your house you are in. Try it now: open the maps app on your phone, switch to satellite view, and zoom in as far as you can. Your phone has a pretty good sense of where on the planet it is (which is pretty amazing if you think about it).

Also, wireless routers know where they are too. So if you connect a non-GPS tablet to the internet via a wireless network (which we all do all the time) you can get some pretty good location data. So just because you don’t have GPS on your device, the capability to get location data is still there.

Now this location data is not inherently bad. As a photographer, being able to tag the location of where I took a photograph is great. How many times have you asked yourself, “Where did I take this picture?” Of course if you’re making the photo public you might not want that information attached to the photo.

The good thing is that as a user, you have the ability to decide which apps have access to your GPS/location data. For things like weather and maps, having those apps know my exact location is a good thing; I want them to know where I am. But maybe not for photos.

Smartphone Settings

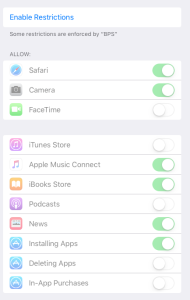

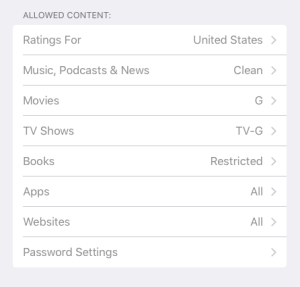

For iOS users (iPhones, iPod Touches, iPads), go into your Settings App. Select the Privacy section and then select Location Services. Here, you can select which apps you want to have access to your location, or you can turn all location data off.

For Android users, go to Settings and select the Location option. Here you’ll be able to manage your Location Services.

How Do I Know What Data is There?

Photo metadata is often referred to as “exif data.” For iOS users, there’s a simple free app called ExifWizard that allows you to view all the metadata for the photos on your camera roll. It also will show positions on a map if that data is provided.

What About Uploading to Social Media?

These days, for better or for worse, most social media sites strip all the metadata out of pictures you upload. Pictures going to places like Twitter, Facebook, or Flickr take all the metadata out. Google+ on the other hand, leaves it intact. WordPress blogs seem to leave the metadata intact as well. There’s a quick article about this here; information about specific social media sites it here. Be aware, these were written from a photographer’s standpoint, so the author wants his metadata kept on his photos so people knows he owns them.

It Doesn’t Have to be Scary

Smartphones are really powerful devices. They do some pretty amazing things. But if we’re going to use them responsibly and safely we need to understand what they’re capable of and how to control them.

We have a rule in my school that if you want to photograph someone with your iPad you must get their permission first. It’s an important rule, but sometimes students break it. This raises an interesting question: if a student is using the iPad inappropriately, should we take the iPad away from them? Since we’re 1:1 with iPads, taking a student’s device away can have ripples of impact.

We have a rule in my school that if you want to photograph someone with your iPad you must get their permission first. It’s an important rule, but sometimes students break it. This raises an interesting question: if a student is using the iPad inappropriately, should we take the iPad away from them? Since we’re 1:1 with iPads, taking a student’s device away can have ripples of impact.

There are lots of things that will make a 1:1 environment (iPads, Chromebooks, laptops, BYOD, etc.) successful, but without ubiquity you won’t find success. If you’re going to go 1:1 technology can’t be an extra thing, it has to permeate everything.

There are lots of things that will make a 1:1 environment (iPads, Chromebooks, laptops, BYOD, etc.) successful, but without ubiquity you won’t find success. If you’re going to go 1:1 technology can’t be an extra thing, it has to permeate everything.

Somewhere, a loving parent takes a picture of their child with a smartphone and posts the picture online. Some nefarious individual gets a hold of the picture and hacks into it to figure out exactly where the picture was taken. The region finds itself in the grips of an Amber Alert.

Somewhere, a loving parent takes a picture of their child with a smartphone and posts the picture online. Some nefarious individual gets a hold of the picture and hacks into it to figure out exactly where the picture was taken. The region finds itself in the grips of an Amber Alert.