For as long as I can remember, my dad has been a math teacher: elementary school, middle school, high school, and for the past 22 years as an independent consultant. As such I have fond memories of sitting in Pizza Hut booths as a kid being posed math questions as we waited for our dinner. As I solved them I was guaranteed to have the follow-up question, “how do you know?” I came to expect it.

At the time, the questions bugged me. “I just do” I would often respond. If I got the question right, why did it matter? Years later as I went through my teacher prep program and began teaching I realized the value of the question and now subject my students to the same question.

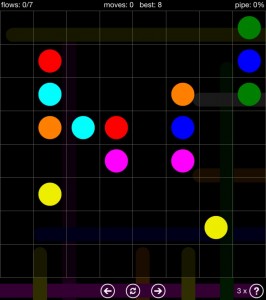

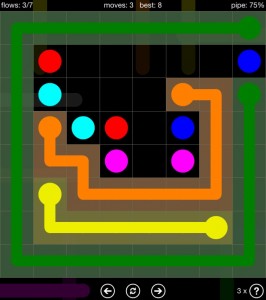

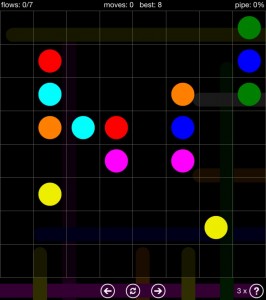

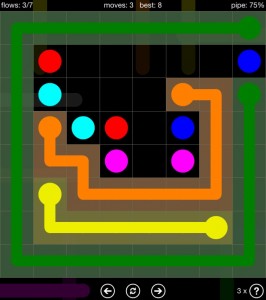

Coming back from the holidays on a long bus ride I found myself killing time on my iPad with Flow (an iOS app). It’s a game (albeit one based on spacial puzzles) I’ve played before and I’ve developed strategies. The idea is to connect the dots, without having any of your lines cross. At times I let my students use the app in school and it’s always interesting to see who takes off with it and who struggles (that is to say, who has a strong spacial sense and who struggles in that area).

Coming back from the holidays on a long bus ride I found myself killing time on my iPad with Flow (an iOS app). It’s a game (albeit one based on spacial puzzles) I’ve played before and I’ve developed strategies. The idea is to connect the dots, without having any of your lines cross. At times I let my students use the app in school and it’s always interesting to see who takes off with it and who struggles (that is to say, who has a strong spacial sense and who struggles in that area).

As I played I got to thinking, if someone asked me about one of the puzzles, “how do you know?” or “can you explain your thinking?” how would I respond?

So I went with the Explain Everything tactic. If I could layer speech (a verbal explanation) over what I was doing in the game, in real time, could I explain what I was doing? That seemed reasonable.

My initial strategy of filing in the outside squares was easy to explain, but then I just found myself seeing the board three or four moves ahead of where I was. Half of the flows would be complete, and I would instantly see the rest. The metacognition we ask our students to do wasn’t working because I wasn’t actually thinking. My eyes saw the board as a whole and my fingers quickly traced around the iPad screen. I was sitting back watching my brain bypass rational thought. It just knew.

My initial strategy of filing in the outside squares was easy to explain, but then I just found myself seeing the board three or four moves ahead of where I was. Half of the flows would be complete, and I would instantly see the rest. The metacognition we ask our students to do wasn’t working because I wasn’t actually thinking. My eyes saw the board as a whole and my fingers quickly traced around the iPad screen. I was sitting back watching my brain bypass rational thought. It just knew.

So if I, an educator with strong spacial skills, can’t explain my spacial thinking is it fair to require all my students be able to explain all their thinking all the time? (Yea, that question made me a little uncomfortable too, which may or may not be a bad thing.)

So if I, an educator with strong spacial skills, can’t explain my spacial thinking is it fair to require all my students be able to explain all their thinking all the time? (Yea, that question made me a little uncomfortable too, which may or may not be a bad thing.)

Ok, I’m not saying we should stop asking kids to explain their thinking. And I’m not going to stop asking my kids to explain theirs. It’s a good question and one we should be asking. But everybody’s brain is different. We’re all wired in different ways. We all remember Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences. Is it possible that “I just know” really is what’s going on in a kid’s brain? Just because we have to think about it (and can be metacognative because we actually are thinking) is it inconceivable that the brain of a student might be wired so differently that they just see what comes next? That they truly don’t have to think about it? That they really just know?

I think it is possible. And I think it happens enough that we need to be aware of it. There are a lot of elementary teachers out there who are especially strong in the linguistic intelligence. If we’re going to help all our students be successful, we need to be open to the idea that we will have students who are stronger in some intelligences than we are, even in elementary school. It’s a wiring thing.

So, the next time a student tells you they just know, take a moment. Maybe they do. Maybe their brain is wired very differently than yours. Maybe it’s the truth: maybe they do just know.

I wanted to defend the iPads, but I couldn’t help but acknowledge some truth in what she was saying. Though it wasn’t that they weren’t interacting with the content, it was just a different interaction. iPads are “mistake tolerant” (Beth Holland mentioned this a lot at the EdTechTeacher iPad Summit), so interacting with them is different.

I wanted to defend the iPads, but I couldn’t help but acknowledge some truth in what she was saying. Though it wasn’t that they weren’t interacting with the content, it was just a different interaction. iPads are “mistake tolerant” (Beth Holland mentioned this a lot at the EdTechTeacher iPad Summit), so interacting with them is different.